April 5, 2021

Does AI make financial markets more informative?

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the exponential growth of data is transforming the way investors value companies. The techno-optimist view is that AI-augmented investors have a greater ability to forecast corporate success and identify valuable companies. This makes stock prices more informative about companies' prospect, which, so the argument goes, is socially valuable because informative stock prices provide accurate signals for resource allocation.

This virtuous effect of AI hinges on the assumption that AI has made financial markets more informative. But does this assumption hold true in reality?

To assess whether stock prices have become more informative as AI was deployed in financial markets, we need an objective way to measure stock price informativeness. To be specific, we need a measure of whether the stock price of a company today is a good predictor of the profitability of the company in the future yet. Answering this question for today's stock prices is not possible because we do not know the future. However, it is possible to determine whether the stock market was informative in the past because, with the benefit of hindsight, we know today whether stock prices in the past were right or wrong.

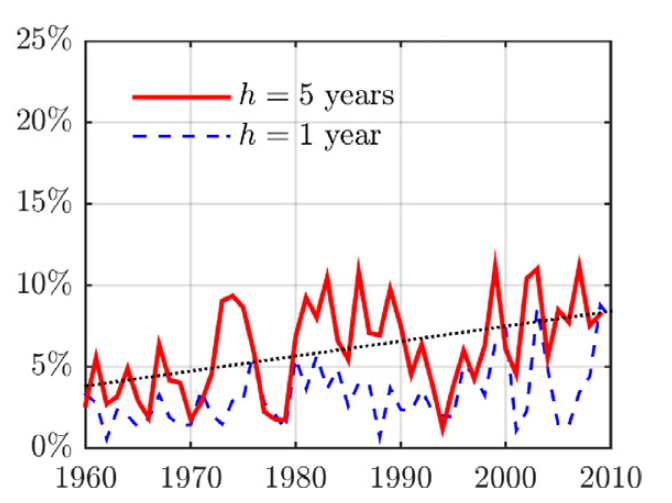

In an article published in 2016 in the Journal of Financial Economics, three researchers[1] followed this idea to assess whether the US stock market has become more informative over time. Figure 1 from their article shows the evolution of stock market informativeness over 50 years. A note at the end of this post explains how exactly the researchers constructed the measure of informativeness.[technical note]

The data shows a clear positive trend in stock market informativeness. That is, stock prices have become more informative over time. One point for AI!

We can also notice that the positive trend predates the widespread adoption of algorithms in finance in the early 2000s. The reason is that information processing costs have steadily decreased over time through the computerization of the financial industry well before the arrival of AI. Therefore, AI continued a pre-existing trend rather initiated a new trend.

However, more recent research brings a more nuanced view of the impact of AI.

Big data for big firms

In an article forthcoming in the Review of Financial Studies, a team of four other researchers[2] confirm that stock prices have become more informative for large listed firms, but the trend goes the opposite way for mid caps and smaller firms outside the S&P 500.

Their explanation is that large firms generate of lot data as a result of their extended economic activity and AI is very good at forecasting in data-rich environments. In contrast, smaller firms and younger firms generate less data and have shorter histories of earnings statements that can feed algorithms. As a result, AI has not been —or not yet—as useful at improving the precision of investors' forecasts regarding the value of small firms.

The fact that improved informativeness is concentrated on large firms may be good or bad depending on how you look at it. On the positive side, large firms make up a large share of the economy, so informative stock prices for large firms have a large impact on the efficiency resource allocation. On the negative side, a great deal of innovation happens in new firms. It is therefore important that markets provide accurate signals about which new firms have good prospects. From this perspective, the trend in stock market informativeness is not as good.

Artificial Intelligence for the short term, Human Intelligence for the long term

In a new working paper, three other researchers[3] extend the analysis until the very recent period and uncover a striking pattern. They find that since the early 2000s, which corresponds to the widespread adoption of algorithms in finance, the forecasting accuracy keeps on improving for short-term earnings but there is a reversal in the forecasting accuracy of long-term prospects. Financial markets become better and better at predicting the short term but worse and worse at predicting the long term.

Their explanation is that alternative data crunched by algorithms predominantly contain information about firms' short-term prospects. Internet data like the number of visits on a retailer's website contains information mostly about next quarter earnings. In contrast, forecasting long-term prospects requires human judgements to anticipate and understand firms' strategic and innovation choices.

This trend—if confirmed—is unfortunate. The near future will be known soon by definition, so information about the near future brought about by financial markets is not so useful for corporate managers and entrepreneurs. In contrast, information about the long term is more important for allocating resources. For example, the extent to which climate risk is accurately reflected in asset prices determines how quickly capital markets allocate capital away from sectors exposed to climate risk .

Sources + Research at HEC

[1] The article taking a long term-perspective on market informativeness is Bai, Philippon and Savov, 2016, Have Financial Markets Become More Informative? Journal of Financial Economics [pdf]

[2] The article on large firms versus smaller firms is Farboodi, Matray, Veldkamp and Venkateswaran, 2020, Where Has All the Data Gone? forthcoming Review of Financial Studies [pdf] Adrien Matray is a graduate of the HEC Grande Ecole and PhD programs, now Assistant Professor at Princeton.

[3] The working paper on short-term versus long-term forecasting accuracy is Dessaint, Frésard and Foucault, 2020, Does Alternative Data Improve Financial Forecasting? The Horizon Effect [pdf] Olivier Dessaint is a graduate of the HEC PhD program, now Associate Professor at Insead. Thierry Foucault is Finance Professor at HEC and scientific co-director of the Hi!Paris Center that studies applications of articifial intelligence in finance and other fields.

Technical note. To construct their measure of price informative, Bai, Philippon and Savov estimate a model that forecasts future earnings based on current accounting information. They calculate the R-square of the model, which measures how well the accounting variables used in the model predicts future earnings. They then add the current stock price to the model, re-estimate it, and look at how much the R-square improves. The increase in R-square between the model that does not use the stock price information and the model that does (called the partial R-square) measures the contribution of the stock price information to forecast future earnings. This is what is plotted in Figure 1. The red line corresponds to the model forecasting earnings at a five year horizon and the blue line to the model forecasting earnings at a one year horizon.

Previous post: What is happening with GameStop »

Next post: Do stock prices affect corporate investment? »

Home »